Click Here for Details

Challenging the Tongue Taste Map

©Richard Gawel

....Email this article to a friend....

I recall attending my first lecture as a winemaking student in the subject Sensory I proudly being displayed on the OHP boldly showing areas of maximum sensitivity to the basic tastes. I found the concept of the "tongue map"

appealing in its simplicity. Everything seemed to tidily fit. There were different types of

papillae located, broadly speaking, on different areas of the tongue, and there were four

taste primaries. Surely each type of papillae contained different receptors tuned

to detect one of the four basic tastes. A corollary to this was that the tongue

must therefore contain regions that are sensitive to one of the four taste

primaries. Although this was never stated in lecture, this fact was implied, and in any

case we all left the lecture thinking that this was the case.

That map was the only diagram given in the entire lecture program that was not

sourced to published work. Why should it be? Like the Mona Lisa

everyone knew it and had seen it (many in primary school science class). Why

clutter the argument with issues such as where it came from! I recall the lecturer

stating that it arose from some work "around the turn of the century". Well

if it’s been around that long it must be correct I thought. However I did feel ill at ease when

I noticed that the tongue map was not included in important and respected sensory

works such as the classic "Principles of the Sensory Evaluation of Food"

by Amerine, Roessler and the highly respected sensory scientist Rose Marie Pangborn. Nor was

it in the then sensory blockbuster and now modern classic "Sensory Evaluation

Practices" by Stone and Sidel. But like most students I answered the inevitable question about

the tongue map that arose in the exam, stored the facts in memory and moved on.

Many years later I were to read a paper by Virginia Collings (Collings, 1974) describing

the variations across the tongue and soft palate in both

detection threshold and in the ability to discriminate between realistic taste intensities.

Collings found that there were variations in detection threshold around the perimeter of the

tongue for sweet, sour and salty but these variations were small and of no practical

significance. The bitter stimuli studied were more easily detected, not on the back of the tongue,

but on the soft palate which resides on the roof of the mouth above the back of the

tongue (yes there are taste buds there). She also reported that differences in suprathreshold

concentrations of the bitter substances studied were more easily resolved on the back

of the tongue. The suprathreshold sensitivity to the other basic tastes, like

absolute sensitivity, varied little across the other parts of the tongue.

So why the contradiction with the earlier work? Well as it turns out the contradiction was

only an apparent one. The "work from the turn of the century"turns out to be a PhD thesis

written in German by Hanig and published in Philosophische Studien in 1901. This paper

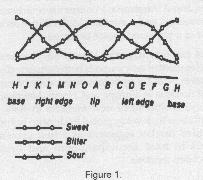

includes a diagram (Fig 5) and reproduced here in Figure 1. The y axis represents the

reciprocal of detection threshold, a measure of sensitivity. Note however that the diagram

is purely qualitative in that the y axis is scale-less. The figure was purely impressionistic.

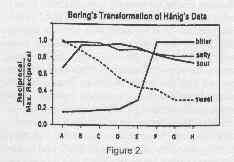

Later in 1942, Boring took Hanigs threshold data and summarised it as a percentage of

maximum sensitivity (reproduced in Figure 2). A cursory glance at both these figures would

lead you to believe that there is substantial sensitivity variation across the tongue. However

neither diagram clearly shows the actual absolute differences in threshold. In fact the

differences observed by Hanig were quite small and of no practical significance. The

interested reader can consult Bartoshuk(1993) for a more detailed account of the

origins of the taste map.

Electrophysical studies, whereby

electrical activity of taste receptors is measured in the

presence of taste stimuli, also support these interpretations.

They show that the vast majority

of taste receptors fire electrical signals, and hence elicit a

taste sensation, in the presence of

all the basic tastes. So much for receptor specificity, the

cornerstone concept underling the taste map.

As a wine and general sensory

educator I believe that this issue gets far more attention that

it

deserves. If one steps back and considers how the taste map (whether

correct or not) helps us

to assess wines, the only conclusion that can be drawn is that it

is of little practical use. Firstly,

the ability to detect tastes at threshold has been shown to be

poorly correlated with suprathreshold

sensitivity. As the majority of the compounds resulting in the

basic tastes in wines are found in

concentrations well above threshold, the practical worth of

knowing variation in detection thresholds

is questionable. Secondly, we can only apply the taste map if we

can effectively localise tastes on

the tongue. But can we do this? If you take a cotton wool bud and

soak it with a strong salt solution

and run it from the tip of your tongue, where receptors are

plentiful, to the middle where they are

very scarce, you will notice that the taste intensity does not

diminish as you might expect. As this

simple illustration of a common taste illusion is analogous to

wine moving across the tongue whilst

tasting, it is unlikely that we as humans can easily localise

tastes in realistic tasting situations.

Perhaps as wine educators we

should tell our students about things that really affect our

ability

as wine tasters. Examples are, the enormous variability between

individuals (many hundred fold) in the number

and distribution of taste receptors, which has been shown to

directly affect how strongly we perceive

tastes. Secondly individuals differ markedly in the amount and

rate of saliva they produce, and this in

turn has enormous implications for our perception of bitterness,

sweetness, saltiness, astringency and

particularly sourness. Lastly and more fundamentally, our

perception of a complex product such as

wine is determined by the interaction of tastes, aromas and

tactile sensations produced by the

various wine components. Knowledge of the nature of these

interactions is where I believe the

real focus of wine tasting education should lie.

REFERENCES

1. Bartoshuk, L. M. 1993. The

biological basis of food perception and acceptance. Food Qual.

Pref. 4:21-32

2. Boring, E. 1942. Sensation

and perception in the history of experimental psychology. New

York: Academic Press

3. Collings, V. B. 1974. Human

taste response as a function of location of stimulation on the

tongue and soft palate. Percep. Psychophys. 16:169-74

4. Hanig, D. P. 1901. Zur

psychophysik des geschmacksinnes. Philosophische Studien

17:576-623